The AI Gold Rush: Biking Mississippi and Louisiana, Part Two

Writing by Michael Chase, Drawings by Jenny Hershey

We met Angela at the security checkpoint for the River Bend Data Center in West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana. Construction had begun only a few weeks earlier, so the job was still new to her. At 64, Angela seemed more preoccupied with dodging relentless Medicare sales calls than screening the contractors driving into the site. She was happy to chat with us, but stood firm on the rules: no one was getting onto that 650‑acre, $10B construction site without a pass. As far as she knew, the only people entering were engineers from Entergy and Hut 8. She told us everything she could about the project - which wasn’t much - but she turned out to be a gold mine once the conversation shifted to Louisiana food. She knew exactly what we should eat and where to find it; we’re pretty sure her employers have no idea they hired a local culinary expert to guard their gate.

Prologue

This is Part Two of a two-part series. It grew out of a trip that Jenny Hershey and I have just taken through Mississippi and Louisiana in January 2026. There is a lot to learn and say about data centers, and these pieces only begin to scratch the surface.

As we crossed from Mississippi into the floodplain of eastern Louisiana, we drove past wintering cotton fields and poverty‑stricken towns. The landscape felt both quiet and alive; abandoned building after abandoned building slumped into the stillness of flatlands where bayous wandered through the low ground, their surfaces ruffled by drifting leaves, dragonflies, and the distant hum of an occasional pickup easing down a gravel road. That hush ended abruptly on the approach to the construction site of Meta’s largest‑ever data center campus outside Rayville, some 35 miles west of Tallulah. If you think of electricity at scale, it is hard not to be either impressed, or horrified, by a campus designed to deliver more than 2.2 gigawatts of computing power. The Gulf South has long moved to the rhythms of egrets, insects, and cotton fields, but a new, more urgent cadence now hums through its humid air. Beyond the bayou, a high‑voltage gold rush of the digital age is taking root.

These monolithic data centers - the unseen engine rooms of our networked lives - rise in stark contrast to the Delta’s ancient soils. Their windowless walls hold a buzzing, hyper‑fast reality, one that can consume the region’s stores of power and water as swiftly as a summer storm swells a creek. In this collision of worlds, a centuries‑old landscape finds itself abruptly tethered to the sleepless pulse of a global economy. From our car windows, it passes like a vision of the future; from our bicycles, we feel it more keenly as a faint, persistent ache, the sensation of watching a living world subjected to degradation by humanity’s unrelenting impulse to control it.

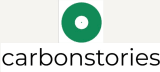

The blue line shows the route we drove by car. We spent many days biking in and around Jackson and Vicksburg, Mississippi, and St. Francisville, Louisiana. The red dots mark the data center sites we visited. All of them are either in the planning phase or in early construction, and none yet have buildings on site.

The New Gold Rush

AI and cloud computing are no longer just tech buzzwords; they are the engine of the modern world. This shift has unleashed a massive building boom of “digital factories” across the U.S., rapidly reshaping physical and political landscapes. For years, Northern Virginia was the epicenter of this buildout; now the region is running up against hard limits: land, power, and water are all in short supply.

As those constraints tighten, Big Tech has turned to a new playground: the Gulf South. Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi are emerging as the next frontier for the “infrastructure of intelligence.” This move is no accident. Tech giants gravitate toward the South and Midwest for one overriding reasons: speed. Coastal regions are bogged down by high costs, local resistance, and complex permitting, while states like Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas are rolling out the red carpet with “shovel‑ready” megasites beside high‑voltage transmission lines, plus generous tax breaks and fast‑track approvals that can shave years off construction.

That competition has sparked a legislative arms race between neighbors. In Mississippi, lawmakers have passed the “Superpower” incentive package, designed to make the Delta irresistible to hyperscalers. Its centerpiece is a sweeping sales and use tax exemption that can stretch up to 30 years - letting a $10 billion AWS campus sidestep hundreds of millions in taxes on the very servers and cooling systems that must be replaced every few years. Across the border, Louisiana is refitting its long‑standing Industrial Tax Exemption Program, once aimed at refineries and petrochemical plants, for the digital age. The state can offer a decade of property tax relief, but there is now a twist: local parishes have a say in whether those abatements go through, producing a patchwork of deals where some communities, hungry for “new economy” prestige, are ready to give away the farm while others are starting to question whether a low-employment data center really justifies decades of lost revenue.

Cypress knees jut out of the water near Tallulah, Louisiana.

Not everyone is cheering this transformation. Some advocacy groups and local organizers describe the rush as a form of “digital colonialism,” arguing that tech billionaires are targeting rural, economically fragile communities with limited political leverage to say no to projects that demand vast acreage, huge water withdrawals, and expensive grid upgrades. For the Gulf South, the pattern is familiar. Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi have long been rooted in extraction - where rapid industrial growth typically outruns environmental protections. Oil, gas, timber, and water are treated first as business assets to be tapped rather than as interconnected ecosystems to be protected. The result is a digital gold rush in which corporate savings are astronomical, while the costs of new transmission lines, substations, and environmental strain often land back on the local community.

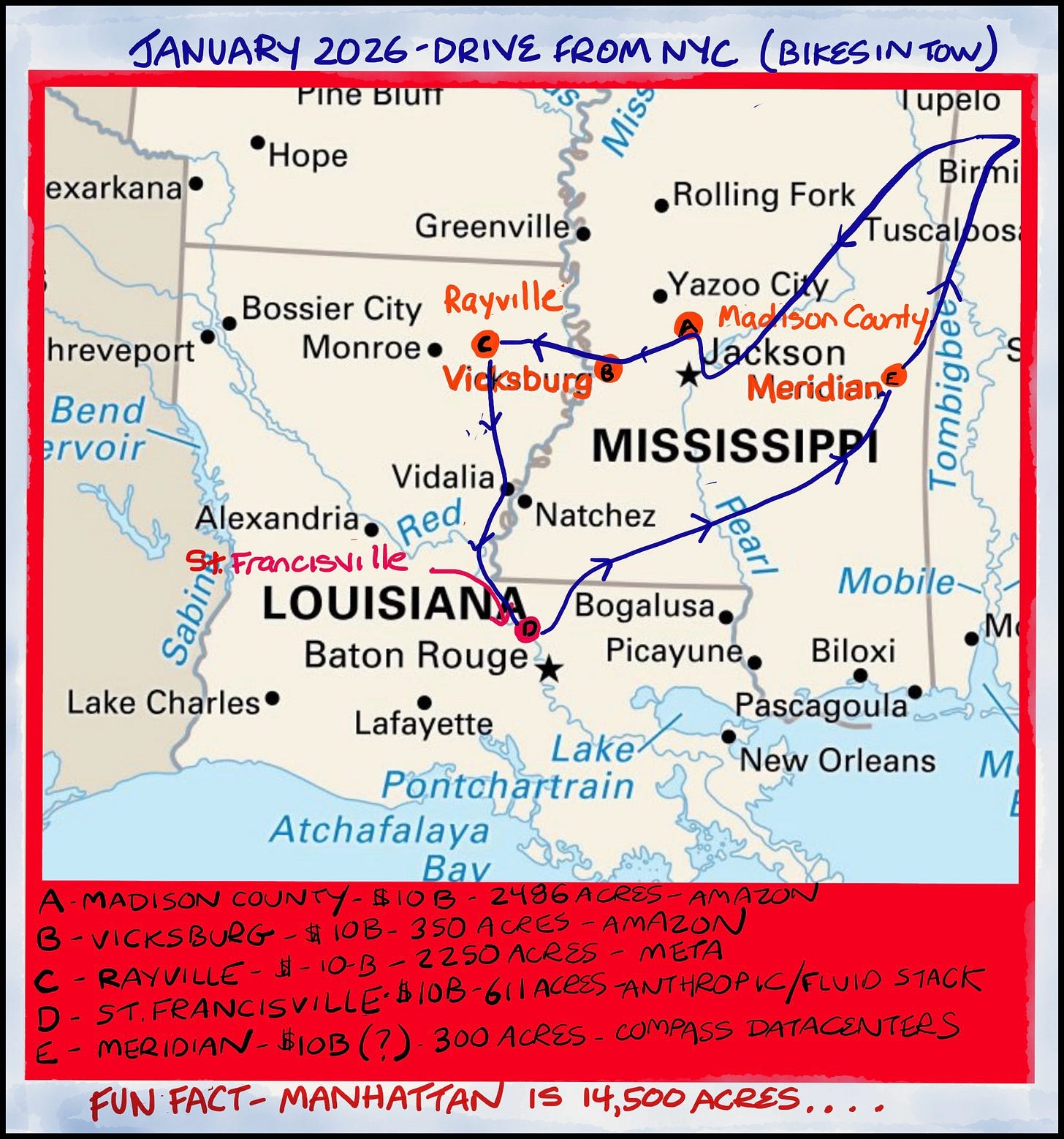

No local story about data centers can be fully grasped without understanding the national context. This map was developed by NREL and adapted by visualcapitalist.com. It can be sourced here.

Rayville and Meta

Meta’s $10 billion bet on the Hyperion campus near Rayville is not just another warehouse of servers; it is an “AI factory” built to train the next generation of large models, including Llama 4, Meta’s bid for so‑called “superintelligence.” These systems are intended to tackle complex reasoning tasks at a scale and speed that can exceed human capacity, and by planting this massive cluster in Richland Parish, Meta positions itself to handle the computational heavy lifting for billions of WhatsApp and Instagram users at once.

This video shows about 2.5 miles of the 4.5‑mile length along one side of the Meta data center site. Filmed from a car window, it’s a bit rough, but it conveys the immense scale of the place. Roughly one sixth the size of Manhattan, it’s genuinely challenging to wrap one’s mind around. In fact, President Trump inexplicably claimed this center will be the size of the entire island of Manhattan (and cost 50 billion dollars) in his speech at Davos in January 2026. Apparently, the project challenges his mind even more.

To understand the impact of this “AI factory,” it helps to look closely at the towns surrounding the site. In places like Tallulah and Rayville, with populations in the low thousands, the demographics are predominantly Black and median household incomes often hover around $24,000. These communities have deep roots but very thin wallets, which is why a project of this scale lands like a thunderbolt. Even in the town of nearby Delhi, where incomes are somewhat higher, double‑digit unemployment feeds an urgent hunger for the prosperity Meta has promised.

Drive past the site today and you’ll see equipment branded with out‑of‑state names like UCS (Utility Construction Services), brought in to manage the project’s enormous power needs. Despite the thousands of workers on‑site, the “upskilling” available to locals often feels more like a whisper than a roar. Much of the best‑paid, highly technical construction work is handled by national giants such as Mortenson and Turner, companies that move from one megaproject to the next with their own traveling crews, while residents from nearby towns like Rayville are more likely to find work in the support economy - hauling materials, pouring concrete, or staffing security and catering.

A street in Rayville, Louisiana, several miles west of the Meta Data Center.

This transformation cuts both ways. Meta highlights that it has spent nearly a billion dollars with Louisiana businesses, but those dollars frequently flow toward established firms in larger cities like Baton Rouge or New Orleans rather than to small shops in Rayville. The permanent jobs - roughly five hundred positions that will remain after construction - typically require technical certifications many locals do not yet have. Meta is partnering with Louisiana Delta Community College and the LED FastStart program to train technicians, but there are no requirements that those trainees be hired from the neighborhoods closest to the campus.

In the process, the project is quietly rewriting the DNA of these rural communities. The sudden arrival of several thousand workers has pushed local rents sharply upward, and families in Richland Parish have already reported being forced out of trailer parks to make room for out‑of‑towners who can pay more. The region’s quiet, agricultural rhythm is giving way to a nonstop industrial buzz. As Meta builds its factory to power a global digital future, many of the people living in its shadow are left to wonder whether they are true beneficiaries of this new era or simply bystanders.

St. Francisville

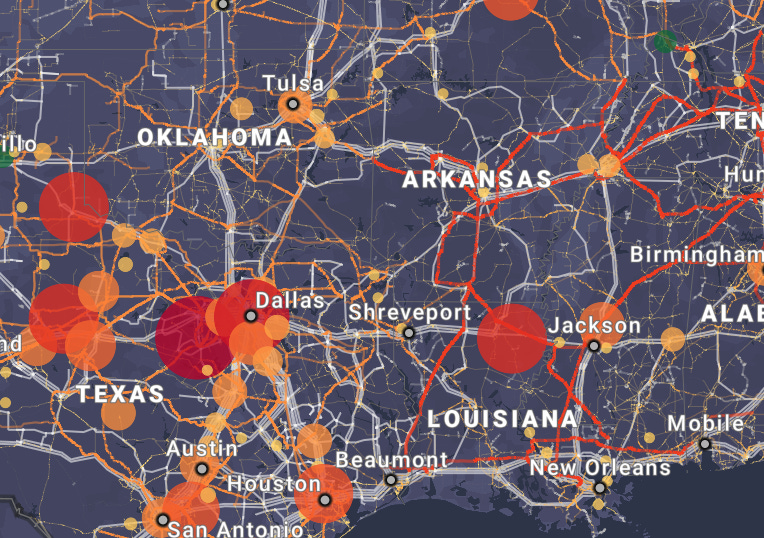

As we dropped south from Rayville to St. Francisville, we could feel the air grow noticeably heavier and warmer, trading the open agricultural expanses of the upper Delta for the dense, humid embrace of cypress swamps and sprawling live oaks. We could feel the ecological shift in our lungs - the transition into a landscape defined by water and ancient, towering wood. We spent our first day here biking through the Cat Island National Wildlife Refuge.

We took a break from our data center research to explore the scenic backroads of the Cat Island National Wildlife Refuge, a protected area established in 2000 near the Mississippi River in West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana. Nestled near the river, this landscape offers a rare glimpse of Louisiana’s original bottomland hardwood habitat. While out biking, we encountered Bert, an enthusiastic bow hunter who was “closing shop” for the season, carefully retrieving his strategically placed tree stands. Bert, a contemporary of ours, explained that he and his companions once kept a hunting camp along the river’s edge, long before the land became part of the national wildlife refuge. After state and federal partners moved to protect the area as a refuge, the hunting camp was removed, a change Bert recalled without bitterness. Now a retired house builder, he has time to hunt but must follow refuge regulations and confine his efforts to designated hunting zones, relying on archery equipment rather than firearms for deer. Despite these constraints, he described the season as a success, proudly noting that two white-tailed deer had filled his freezer and would help sustain him in the months ahead.

Just a short distance from this ancient silence sits the site for the Hut 8 “River Bend” data center. This ten-billion-dollar AI campus is being carved into the West Feliciana Parish landscape, specifically chosen for its proximity to the River Bend Nuclear Station. The energy for this massive facility will come directly from Entergy Louisiana, which is providing an initial 330 megawatts of capacity - roughly a third of the nuclear plant’s total output - to power high-performance computing for names like Anthropic and Fluidstak. As the site scales toward its potential one-gigawatt capacity, it will effectively become it’s own private “power island.”

The water issues surrounding a project of this scale are usually the first thing people worry about, but the Hut 8 design is pivoting toward a closed-loop, recirculating system. Unlike the older evaporative cooling methods that can swallow millions of gallons a day, this setup acts more like a car radiator. The initial “fill” requires a significant amount - roughly the volume of four Olympic swimming pools - but after that, the ongoing water draw will supposedly be limited to basic facility needs. It’s an attempt to mitigate the kind of aquifer depletion that has sparked controversies elsewhere, though the sheer heat generated by these racks still requires an enormous amount of energy to move that water around the loop.

A healthy Jenny stands at the base of a 1,500-year-old national champion bald cypress in Cat Island National Wildlife Refuge. This ancient giant, which survived the era of post–Civil War cypress logging, is a living bridge to prehistoric Louisiana. Rising nearly 100 feet high and measuring 56 feet in circumference, it is a breathtaking feat of natural architecture that anchors this fragile, flood-prone sanctuary.

The most pressing concern surrounding the HUT 8 data center is how this industrial titan will coexist with its neighbors: the nearby Cat Island National Wildlife Refuge and, just to the north, the Old River Wildlife Management Area. These protected lands serve as vital stopovers for migratory birds and provide habitat for species such as the swallow-tailed kite. While the data center may not drain the river itself, the constant mechanical roar and light pollution from a facility of this scale threaten to disrupt the very wildlife these refuges were established to protect. Building such a high-intensity complex on the banks of the Mississippi, flanked by wildlife sanctuaries, creates a striking contrast between the timeless stillness of the bald cypress and the frantic, high-decibel hum of the digital age.

Meridian

Most mornings in the countryside of Lauderdale County, Mississippi, near the beleaguered but fascinating town of Meridian, a heavy mist settles over the red clay and the loudest sound is a pileated woodpecker’s hammering. For generations, the county has moved at a quiet, predictable rhythm - a place where the air smells of damp earth and pine resin, and where “growth” usually means another row of trees, not another row of servers. Now, in the middle of that stillness, something very different is taking shape. On the edge of Meridian, at the I‑20/59 Industrial Park where woods once stood largely undisturbed, earthmovers and cranes are turning a quiet patch of pine into one of the largest hyperscale data center campuses in the Southeast.

A Texas-based firm, Compass Datacenters - backed by the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan and Brookfield Infrastructure Partners - is building an eight‑building complex it values at up to $10 billion, including the equipment its future tenants will install. Compass doesn’t just construct these facilities in the traditional sense; it also manufactures them, using prefabricated modules to drop massive, windowless concrete “gray boxes” into rural landscapes at startling speed. Adding a quiet irony to the story, Brookfield Infrastructure Partners L.P. is a publicly traded infrastructure company also headquartered in Toronto, that acquires and manages assets around the world, making this massive Southern data center boom underwritten by Canadian capital.

Because of storm “Fern” we were unable to visit the Meridian site, so we added this stock photo from the Compass Data Center website. You can view their designs for yourself here.

But there’s an even larger irony at work: the $10 billion question hanging over Meridian is who actually plans to occupy these boxes. Compass says eight “powered shells” are being built on a speculative basis, designed for single‑tenant hyperscale clients. No one will say, on the record, who’s coming, but most people assume the usual suspects - Amazon, Google, Meta, OpenAI, Anthropic - must be chasing new capacity for energy‑hungry AI workloads. If those tenants materialize, Meridian becomes a node in the global AI economy almost overnight. If they don’t, Compass and its contractors still collect their fees, while the county is left with a concrete monument to a digital boom that never made it past the marketing phase.

What’s not up for debate is the environmental price tag. At full build‑out, the Meridian campus is expected to pull roughly 500 megawatts of power - enough electricity for about one in five single‑family homes in Mississippi. Demand on that scale doesn’t just show up on a bill; it rearranges the grid. Mississippi Power has already told state regulators it will keep at least one coal unit at the Victor J. Daniel plant running into the mid‑2030s - years past its planned retirement - to cover new data center load. In effect, a project marketed as “modern” tech is helping lock in millions of tons of extra carbon pollution as the rest of the world is trying to move the other way.

National watchdogs say Meridian isn’t an outlier so much as a preview. The Center for Economic Accountability tagged the Compass deal as its “Worst Economic Development Deal of the Year” for 2025, flagging secretive talks, oversized subsidies, and tax breaks that could trim the project’s property tax bill by roughly two‑thirds for decades. Local power brokers, including the East Mississippi Business Development Corporation and Lauderdale County supervisors, hashed out incentives behind NDA’s, ultimately offering 10‑year exemptions from state income, franchise, and sales taxes. For local residents, that means a multi‑billion‑dollar operation could skate by with relatively light taxes in its most profitable early years, even as it leans on public infrastructure and a coal‑heavy power supply.

A forest near Meridian, Mississippi awaits summer.

Beyond Mississippi, more than 200 environmental and community groups - including Food & Water Watch and Greenpeace - are pushing for a national timeout on new data centers until policy catches up with their impact on the grid, water, and rates. They point to signs that wholesale electricity prices in data center hot spots have spiked, with one analysis showing increases of up to 267% in some markets over five years, and warn that regular customers will wind up footing the bill. In Meridian, though, public dissent has mostly been quiet, drowned out by promises of “thousands of jobs” and “once‑in‑a‑generation” investment - even though many of those jobs are short‑term construction gigs that vanish once the last server rack is bolted down.

For Meridian, it all adds up to a high‑stakes bet on the future. On paper, the project brings billions in private money, upgrades to roads and utilities, and, once the tax breaks run out, a potential shot in the arm for the local tax base that leaders say could support schools and public services for years. On the ground, the trade‑offs are harder to gloss over: more coal on the grid, higher emissions, possible pressure on power prices, and the slow erasure of the quiet, wooded character that has defined East Mississippi for generations. The county is effectively trading the steady growth of pine forests for the fast, flickering promises of the digital age, and hoping the lights don’t get too expensive to keep on.

Epilogue

As we leave the shadows of the ancient bald cypresses of Louisiana bayou country and the mists of sleepy Lauderdale County and head back toward the modern world, the silence in these parts feels less like a permanent state and more like a finite resource being mined. The crossroads is a strange one: the same technology that hums with a 100‑decibel roar might also be our best shot at calming the storm of climate change. It is a profound, heavy paradox - are we really required to scar the very places that remind us why the planet is worth saving?

That tension forces some hard questions. Can a machine born from the exhaustion of our aquifers and the industrialization of our quiet truly teach us how to live in harmony with the earth? Or is AI simply the latest, most efficient tool in an old pattern of extraction - a “digital gold rush” that moves wealth from Delta soil onto distant balance sheets? If the spoils of this intelligence only flow upward, will we have traded our natural heritage for a machine that serves a master we can never meet?

Still, it is worth looking at this predicament with a kind of tough love for the human spirit. Our success - our brilliance, our curiosity, our refusal to accept limits - is exactly what brought us to this edge. We built this world because we wanted to connect, to solve, to thrive. Now we are betting on artificial intelligence to help us outrun the weather extremes and degraded environments our own success set in motion.

Some argue that the answer lies not in more silicon, but in more wind and sun - and they are not wrong. But many proponents see AI as the brain that finally makes that body of renewable energy work. Already there are examples that suggest the pattern: Google’s DeepMind has trained neural networks to predict wind power output 36 hours in advance, boosting the value of wind energy by roughly 20 percent and making that variable power as reliable as conventional sources. In Brazil, AI‑guided drones are reforesting hillsides at speeds 100 times faster than human hands, dispersing 180 seed capsules per minute and reaching slopes too steep or dangerous for traditional planting crews. Meanwhile, in the oceans, AI‑powered systems are mapping plastic pollution with a precision that allows cleanup operations to target debris hotspots surgically, using automated image recognition to detect and track floating plastics across vast stretches of open water. These are not small wins - they represent shifts in scale and speed that were unimaginable even a decade ago.

Whether AI actually helps us before the resource clock runs out will likely depend on how we choose to use it: as a replacement for human wisdom, or as a supplement to it. If this power is bent toward building livable, peaceful communities rather than just high‑speed profit centers, there is still a path through. But that path will require valuing the “unproductive” silence of a cypress swamp as much as the “productive” hum of a server rack. We are a species that can build both; the real question is whether we have the heart to let them both endure.

Stay vigilant! Thanks for reading. If you haven’t done so, please subscribe to this blog to follow our next biking trip.

This newsletter was written by Michael Chase, with drawings by Jenny Hershey. Unless otherwise noted, all material is the copyrighted property of the authors, including all photographs and drawings. Jennifer Hershey’s drawings can be enjoyed on Instagram at deeofo.

Sources

The New Gold Rush:

(General & Mississippi)

(Louisiana Context)

Louisiana Economic Development: Industrial Tax Exemption Program

The Lens NOLA: Fears of a Digital “Cancer Alley” in Louisiana

St. Francisville:

Meridian:

Epilogue:

This is some of the most compelling environmental journalism I've read in a while. The framing of 'digital colonialism' really nailed somthing I've struggled to articulate about how these tech giants deliberately target communities with thin wallets and limited bargaining power. When I drive through rural areas back home, I always wonder what development will actually stick around versus just extract andleave. Dunno if these places will ever see the benefits they're being promised.