The AI Gold Rush: Biking Mississippi and Louisiana, Part One

Writing by Michael Chase, Drawings by Jenny Hershey

We met Chris at the security gate of Cam 2 at the Port of Vicksburg, Mississippi, on a chilly Saturday morning. When Jenny asked what was happening, Chris answered with a grin, “Absolutely nothing!” He stood with two friends at the gate, hands in pockets, watching trucks cycle through the port. They seemed content just to be there together. Chris told us he was glad to have steady work, but there was a hint of longing in his voice when he talked about someday riding a bicycle like us. For now, though, gratitude defines his days. When we asked about the huge data centers being built nearby, the three men nodded knowingly. They spoke about friends driving dump trucks, hauling dirt, and clearing land for the construction crews. “It’s good work!” one of them said with pride, and the others agreed. As we pedaled away, we couldn’t help thinking about their easy acceptance. For them, questions about environmental impact or progress seemed distant. Their focus is present and practical: keeping food on the table, staying busy, and saving a little for whatever might come next.

Prologue

If you followed our last post, you know our previous trip ended abruptly after a bicycle accident. We are happy to report that we are back on our bikes again, riding with a bit more caution as our confidence returns. This time, our car was never more than a day’s ride away; we used it to haul our gear for overnight stays, then wandered out to explore local roads on our bikes. While this wasn’t as immersive as traveling entirely on bicycles, it still kept us close to the weather, the smells, and the small surprises of the landscape. Even from a car, driving backroads offers a front-row seat to the vastness of the rural South - a living history written in the pain of human labor and the shade of meandering bayous.

This is Part One of a two-part series. It grew out of a trip that Jenny Hershey and I have just taken through Mississippi and Louisiana in January 2026. There is a lot to learn and say about data centers, and these pieces only begin to scratch the surface.

We already knew many data centers were being built in Mississippi and Louisiana, but seeing them in person changed the scale of our awareness. Both states are about to be dotted with a new kind of architecture: windowless, sprawling monoliths that rise from former fields and forests. We wanted to see how the global thirst for artificial intelligence is reshaping rural America. For the past several years, most conversation about AI has focused on large language models that can chat, code, and create. We are now moving from experimentation to industrialization. If the previous era was about teaching AI to speak, this one is about building the infrastructure for it to live. We are transitioning from the Wright brothers’ first flight to the construction of international airports. To operate at the scale the world now demands, AI needs a physical body of staggering proportions.

The ambition driving this boom is no longer just smarter chatbots. It is about systems that not only talk but act: managing supply chains, diagnosing disease in real time, and running autonomous power grids. That shift demands new infrastructure, moving from dispersed cloud storage to massive, fast, regional hubs. The upside is real. These centers have the potential to deliver large streams of tax revenue to rural communities, funding schools and public works that have gone without investment for decades. But they are also “power-hungry” in the most literal sense. A single AI query can use many times more electricity than a traditional search and, in places like Mississippi and Louisiana, that puts intense pressure on local grids and the water supplies used for cooling.

Why are rural communities embracing this? For many, it looks like a digital harvest. These facilities no longer bring the thousands of jobs that factories used to, but the property taxes alone can transform a small county’s budget. As big tech moves into rural America, it often displaces the very agriculture that defined it. We are watching a landscape where 200-year-old family farms and forests are being erased to house servers that may later guide self‑driving tractors in fields hundreds or thousands of miles away. The irony is hard to miss. Soon, rural America may become a patchwork of “data colonies” - secure, energy-intensive islands of steel surrounded by traditional farmland. This future is arriving at lightning speed, often faster than the regulations meant to protect local land, water, and air.

There is also a personal paradox: as Jenny and I bike these backroads documenting the environmental and social costs of this gold rush, we are leaning on the same AI tools that these centers are being built to support. They help us pull together scattered data in seconds: where centers are being built, what tax breaks they receive, how communities are pushing back, and where information remains opaque. The speed and power that make these tools so productive also drive the expansion we are questioning. Like so many others, we have become critics of the footprint and beneficiaries of the function. More and more, it feels as though we are living inside the very machine we are trying to understand.

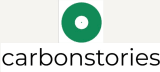

The blue line shows the route we drove by car. We spent many days biking in and around Jackson and Vicksburg, Mississippi, and St. Francisville, Louisiana. The red dots mark the data center sites we visited. All of them are either in the planning phase or in early construction, and none yet have buildings on site.

Jackson

After a long drive from New York City, angling southwest through the Appalachians and the hills of Alabama, we reached Jackson, Mississippi. We stayed in the historic Belhaven district, where a short ride on our bicycles brought us to the infamous J.H. Fewell water treatment plant. Still rebuilding trust for its drinking water in the wake of the 2022 crisis, Jackson has been upgrading its system. There have been some successes, and current plans focus on stabilizing the entire network and strengthening a newer facility, part of a longer arc of recovery that is still very much in progress.

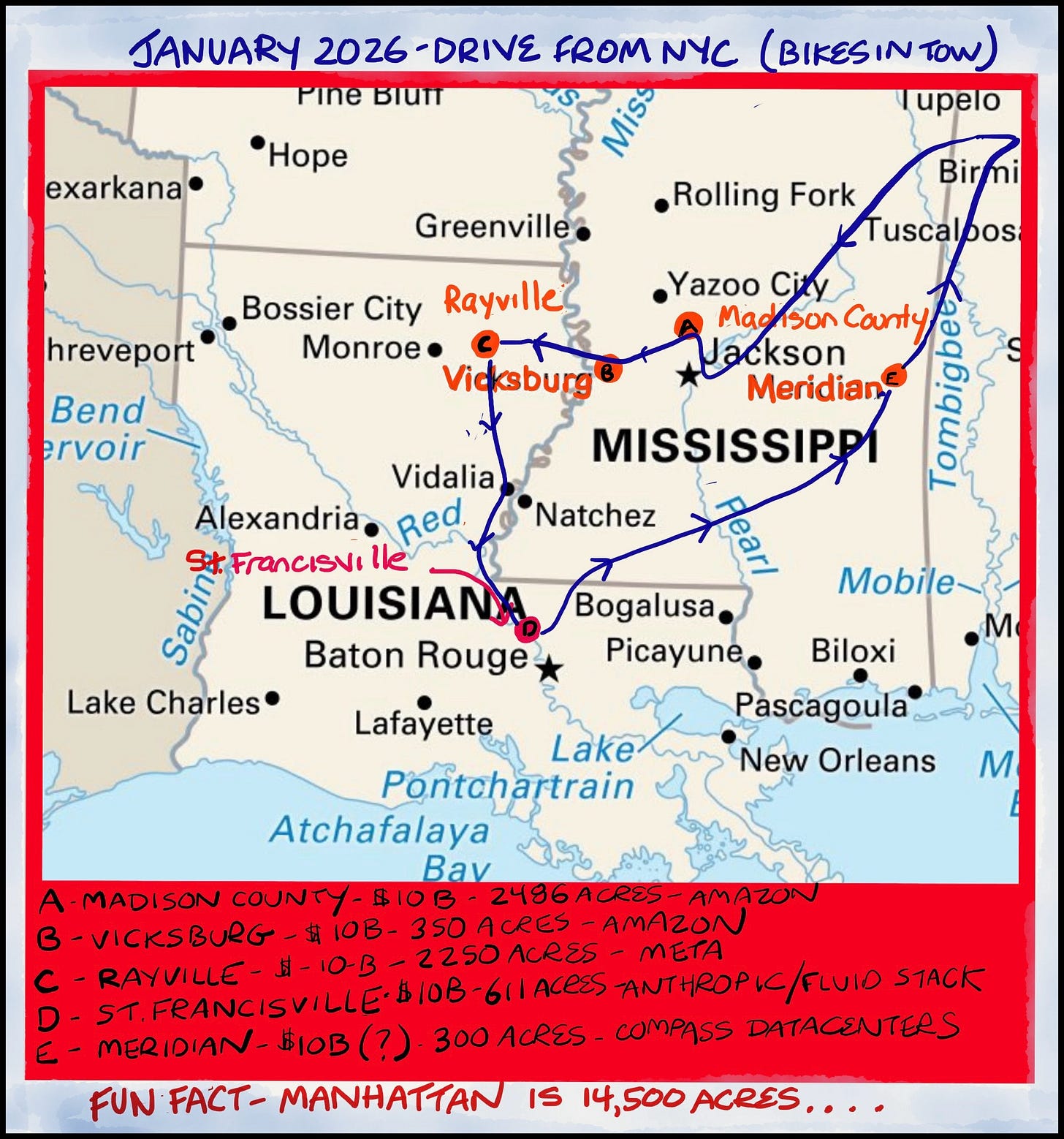

From Fewell, it is a short bike ride into downtown, where the Mississippi State Capitol dominates the skyline. The next day, we spent hours in the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, absorbing stories that weave together land, labor, law, and resistance across Mississippi. Later, biking northeast, we arrived at the Beth Israel Congregation, badly damaged by a recent fire that state and federal authorities are investigating as a hate crime. After the civil rights museum, the blackened walls of the synagogue felt less like an isolated incident and more like another chapter - a reminder that antisemitic and other hate-fueled attacks are not an abstraction, but a pattern inscribed on real buildings, real communities, and real mornings that begin with smoke.

We met Ted in Jackson, standing quietly outside the Beth Israel Congregation, taking stock of the fire damage that consumed the synagogue’s library, including two Torahs, and their offices. At 78, Ted carries himself with quiet pride as the congregation’s longest-serving and oldest local-born member, a retired property manager who still looks after the building as if it were his own. When we asked if they would rebuild, he answered without hesitation: “Of course. We must and we will. We survived the KKK bombing in 1967. We’re not going anywhere.” The temple is now in the midst of a painstaking cleanup to remediate asbestos and smoke damage, while the congregation has been welcomed into a nearby Baptist church that offered its space without a second thought, even preparing to host an upcoming Bat Mitzvah. Standing there with Ted, watching people move in and out of the scarred building, the burned books and blackened walls told one story, but his steady voice - and the open doors of the church down the road - told another: that even in a place marked by old hatreds and fresh wounds, people still choose to show up for one another, and to begin again.

Biking out of Jackson isn’t easy. With little dedicated cycling infrastructure, even short trips feel precarious, and getting across town can be a challenge. We persisted on our first day, but by the second we gave in and drove the twenty miles to the Madison County data center site northeast of the city - one of two massive, linked data center campuses now under construction by Amazon Web Services (AWS) as part of a $10 billion investment in the state. We had already caught a glimpse of one smaller data center construction site near Brandon, but nothing prepared us for the sheer scale of the Madison County project.

However, when it comes to the “economic miracle” promised to the region, the numbers require a closer look. The Madison County project is currently supporting at least six thousand construction jobs, but our drive past the site indicated that many of the specialized workers are not locals; they are transient crews that follow national contractors from project to project. For residents of Jackson, that twenty‑mile distance does not automatically translate into a high‑tech paycheck. Many Jackson‑based workers on-site are concentrated in support roles - site security, hauling, and basic labor - rather than in the high‑skill electrical or fiber‑optic work that commands the highest wages.

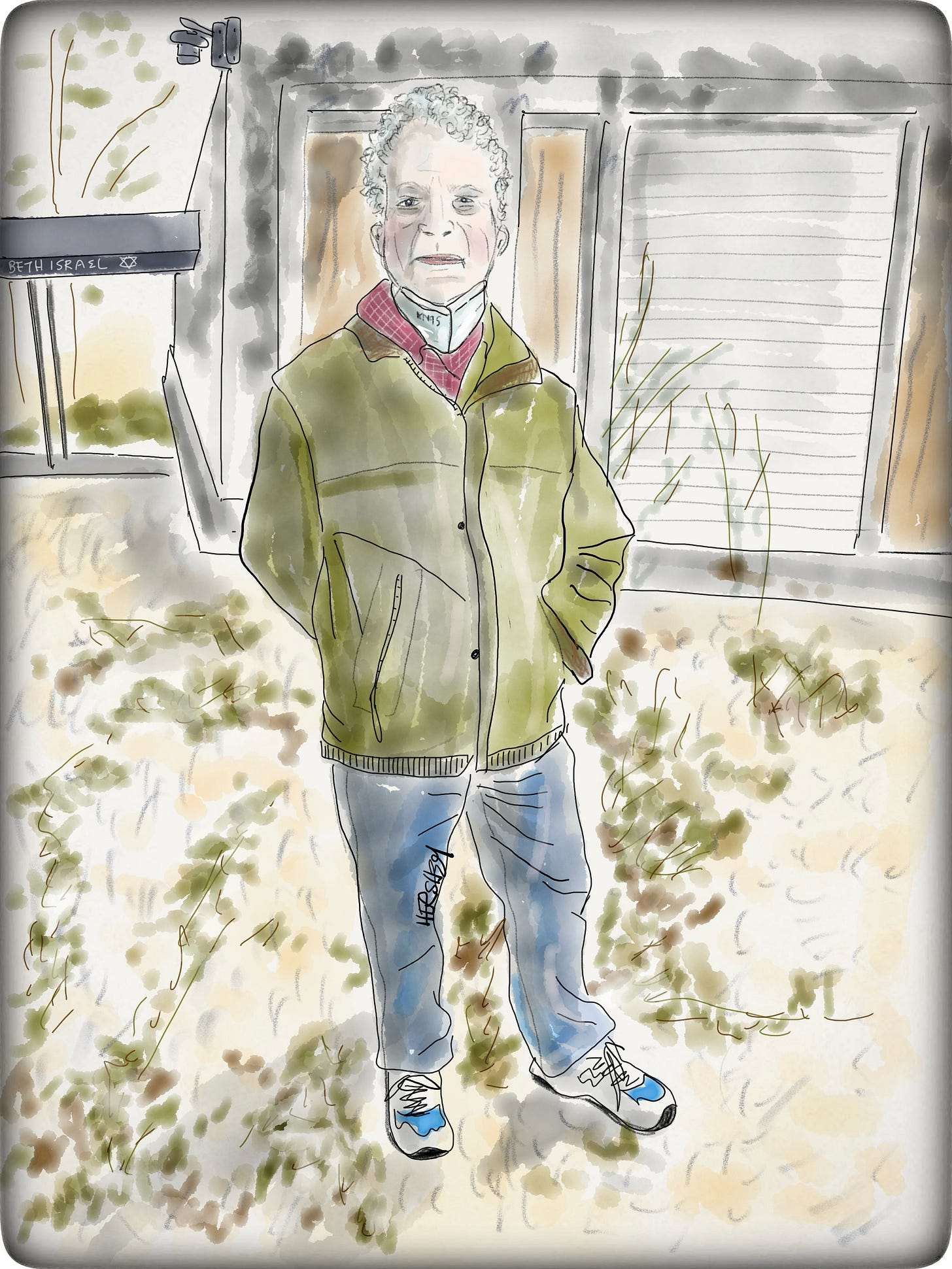

We were fortunate to meet Timmy on an unusually rainy day, while taking shelter under the covered porch of his restaurant on the reservoir in Ridgeland, Mississippi. Although closed, he invited us in to dry off and offered a warm cup of tea. He seemed surprised by our curiosity about the data centers rising in the surrounding area. We asked him about the AWS center under construction in Madison County and what he knew about how it might affect the power grid and local water supply. He didn’t answer, but he smiled and told us he owned sixteen acres very close to the site. Clearly hoping Amazon would ultimately need an even larger footprint, Timmy thought his land might increase in value. We learned he had recently stepped down as head of the county election commission, but before we stepped back into the cold, he made sure to tell us about all the “127‑year‑old people” who had voted in his county. Timmy firmly supports a complete crackdown on mail‑in voting and strict identification requirements for in‑person voting, echoing broader Republican efforts to limit mail ballots in Mississippi and beyond.

As for permanent employment, AWS expects to create at least 1,000 high‑paying jobs across its Mississippi sites by 2034, with average salaries starting around $66,000. To bridge the skills gap for Jackson residents, Amazon has partnered with the Mississippi Community College Board to launch an “AWS Fiber Optic Fusion Splicing Certificate” program - an accelerated course designed to get locals certified in just a few days at places like Hinds Community College. These “pre‑apprenticeship” opportunities are expanding, with thousands of people applying for programs like the one at Hinds. And yet the core question remains: will residents of a city still struggling with its own basic infrastructure see the long‑term benefits of a high‑tech campus up the road, or will they be left instead with the burdens of a more strained power grid while the best opportunities flow to better‑connected suburbanites?

A small slice of the Madison County data center construction site, where Amazon is touting plans to use recycled wastewater for cooling. AWS has announced a nationwide push to cool more than 120 of their U.S. data centers with treated wastewater by 2030, framing the shift as a way to preserve over 530 million gallons of drinking water each year. Yet local critics and national analysts argue that this story obscures the water lost in the cooling process itself. Modern evaporative systems typically consume the vast majority of what they draw - around 80 percent - returning only a fraction to wastewater treatment, raising concerns that “recycled” does not necessarily mean “low impact” in already stressed aquifers and river systems.

Vicksburg, Mississippi and the Louisiana Delta

A few days later while out on our bikes, we climbed westward into the high, wooded bluffs of Vicksburg National Military Park. From the heights, the Delta floor stretches out like an emerald sea - a fertile expanse that has yielded immense wealth for some and profound suffering for others. As we descended onto the long, flat curves of the Delta, we could smell the thick scent of alluvial soil and contemplate the heavy, complicated ghosts of the American South.

View of the river and the Louisiana Delta from Vicksburg National Cemetery.

While the Madison County site in Jackson is a resource behemoth, local environmental alarm bells ring even louder around the smaller AWS site planned for Vicksburg. There, residents are worried about the Mississippi River Alluvial Aquifer (even our hosts at a local Airbnb brought it up), because the facility sits directly atop this critical groundwater source. The concern doesn’t stop at the state line. Between this campus and Meta’s much larger data center complex under construction about 48 miles west in Louisiana (read more on this in Part Two), the combined pressure on the aquifer is significant. Recent modeling by Frank Tsai, director of the Louisiana Water Resources Research Institute at LSU, helps explain why people are paying attention: in a 17‑year simulation of the Meta project, he found that if the data center withdraws its maximum allowed daily volume, groundwater levels could drop by as much as 65 feet. Drops of that magnitude can cause land to sink and increase the risk of saltwater intrusion, raising serious environmental questions about the millions of gallons needed to cool both the Vicksburg and Rayville facilities.

The site of Entergy’s decommissioned Baxter Wilson plant, currently being rebuilt as a $1.2 billion “advanced power station” specifically for the Vicksburg campus. These campuses each require many gigawatts of power, forcing Entergy to fast‑track new natural gas infrastructure just to keep up with the demand.

Not very far south of Vicksburg, the Grand Gulf Nuclear Power Station stands as a monolithic reminder of the region’s long‑standing role as an energy exporter. It is the most powerful single‑unit nuclear reactor in the country, and for decades its massive cooling towers have vented steam into the humid air to power hundreds of thousands of homes. Yet, while the Grand Gulf Nuclear Station is a massive presence on the Mississippi River, it isn’t a silver bullet for the region’s new data center boom. It’s certainly a major player in the regional energy mix, but Entergy isn’t just plugging these new server farms into the existing nuclear plant. Instead, they are essentially building an entirely new, parallel energy infrastructure to meet the staggering demands of companies like Amazon and Meta.

In Madison County, Entergy Mississippi is actually constructing three brand-new power plants specifically to support those operations. To balance the scales, Amazon has also committed to 650 megawatts of new renewable energy, including massive projects like the Sunflower Solar Station. Over in Richland Parish, the energy story for Meta is more localized. Rather than drawing primarily from the nuclear grid in Mississippi, Entergy Louisiana is building a dedicated “mini-grid” right in Richland’s backyard. This includes the Franklin Farms Power Station, a cluster of three gas-fired plants designed to handle a load that is projected to consume more electricity than the entire city of New Orleans. To keep things green (at least on paper) Meta is also tying in about 1.5 gigawatts of solar power to supplement those gas plants. So, while Grand Gulf provides the steady “baseload” that makes the region so attractive to Big Tech, the reality of the 2026 landscape is a frantic scramble to build new gas and solar hubs just to keep the lights on in the server rooms.

There is even talk of adding Small Modular Reactors near the site to create a “nuclear‑to‑server” pipeline. This is some of the richest, most fertile soil in the world - land that has sustained generations through physical toil - yet the technology being built here threatens to erode the very foundation of that life. It is a staggering trade‑off. The Delta’s ancient water reserves and its legendary quiet are being harvested to power a digital world that feels entirely detached from the history of painful human labor along these backroads. For a region that has already given so many physical resources to the wider world already, the loss of its energy, water and its peace may be the final, invisible cost of the cloud.

Epilogue

Finally, in addition to looming concerns over energy grids and water tables, another environmental crisis is emerging that many communities only recognize once the concrete has already set: noise. While local leaders tend to focus on tax revenue and the promise of a “digital harvest,” residents in communities near already functioning data centers are discovering their quiet agricultural landscapes have been replaced by a relentless industrial thrum. This isn’t the occasional rumble of a tractor or the seasonal hum of a harvest; it is an around-the-clock mechanical vibration that never lets up.

On the Delta just north of Vicksburg.

The science behind this "din" is increasingly alarming. While wind turbines are often compared to the hum of a refrigerator, data centers are a different beast. These facilities produce a permanent industrial roar that can rival a jet engine, drowning out the natural sounds of the landscape 24 hours a day. Unlike wind turbines, which average between 35 and 45 decibels at typical residential distances and often blend into the wind itself, the cooling fans and backup generators of a data center can reach levels exceeding 90 to 100 decibels at the source. Because these massive fans are often located on rooftops to vent heat, the sound waves are pushed outward, traveling across flat, rural terrain for miles.

Public health experts and groups like the Sierra Club have begun documenting the toll of this low‑frequency noise. Unlike high‑pitched sounds that can be blocked by insulation or trees, the deep hum of massive HVAC systems vibrates through walls and hits the body as a physical stressor. Residents in places like Arizona and Northern Virginia have already reported a growing list of noise‑related health issues: chronic sleep loss, heightened anxiety, high blood pressure, even cardiovascular strain. For the local environment, that constant noise means animals can’t hear each other, hunt, or find their way as the everyday sound of birds, insects, and wind thins out. As big tech scales up for the AI era, the “silence” of rural America is being traded for a permanent, high‑voltage growl - a reminder that the price of progress is all too often paid in the sounds and spaces of the living world we claim to cherish. Will what we lose be worth what we might gain - and who gets to decide?

Stay vigilant! Thanks for reading. If you haven’t done so, please subscribe to this blog to follow our next biking trip.

This newsletter was written by Michael Chase, with drawings by Jenny Hershey. Unless otherwise noted, all material is the copyrighted property of the authors, including all photographs and drawings. Jennifer Hershey’s drawings can be enjoyed on Instagram at deeofo.

Sources

Prologue:

Mississippi Free Press: Amazon to Build $3B AI Data Center in Vicksburg

Yale Clean Energy Forum: Regulating Digital Giants and Policy Responses

Jackson:

Governor Reeves: Arson Investigation at Beth Israel Congregation

Mississippi Free Press: Jackson Water Progress Since 2022 Crisis

Mississippi Development Authority: AWS to Invest Record $10 Billion

Clarion Ledger: Amazon to Invest $10 Billion in MS Data Centers

Vicksburg and the Louisiana Delta:

Union of Concerned Scientists: What’s Next After Louisiana’s Gas Plant Approval for Meta

Hut 8 Selects Southeast Louisiana as Site of $10 Billion AI Data Center

Pelican Policy: What’s Ahead for Data Centers and Energy in Louisiana

Epilogue: