The Silence Before: Biking and Survival in the Appalachian Highlands

Writing by Michael Chase, Drawings by Jenny Hershey

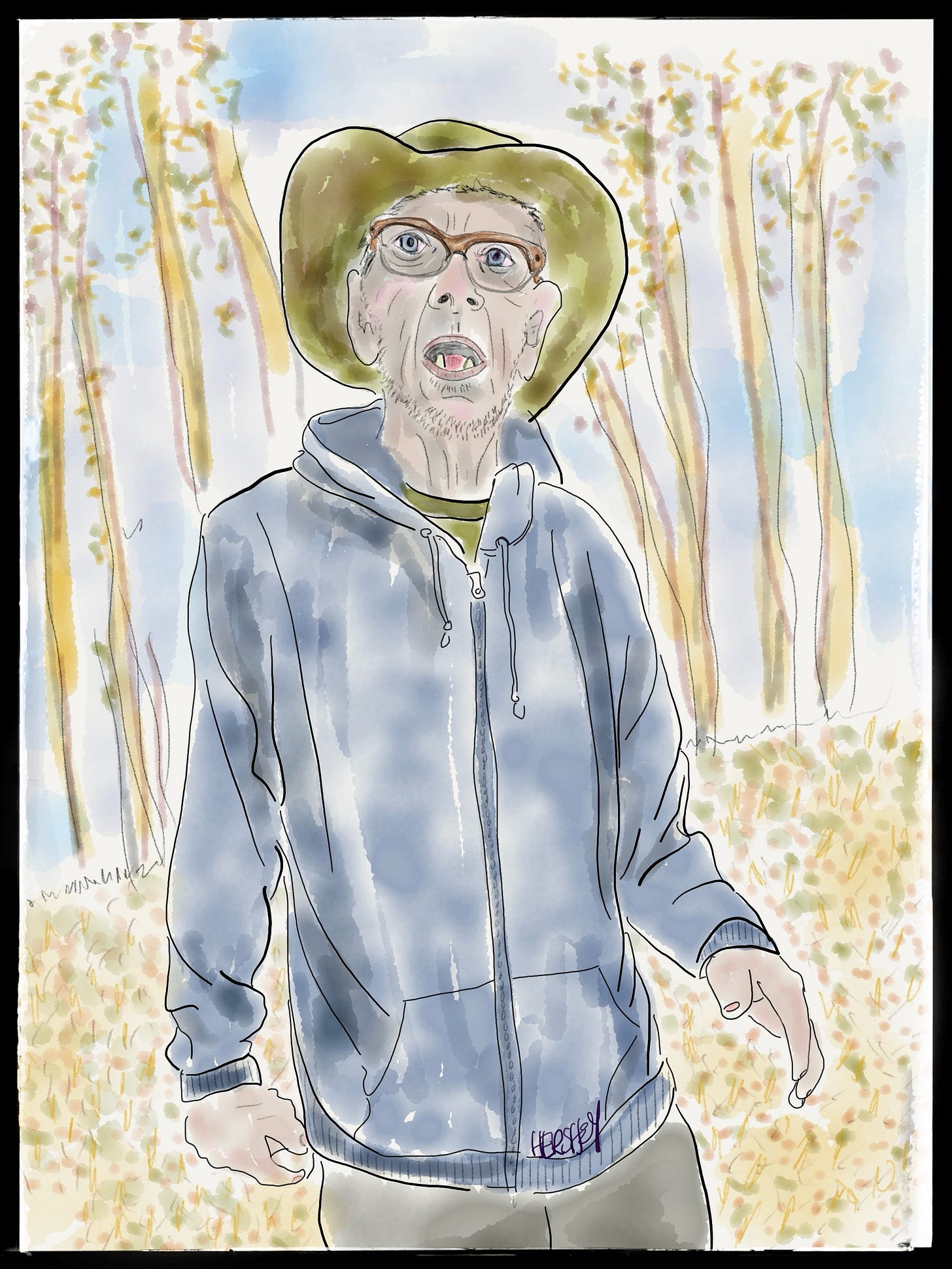

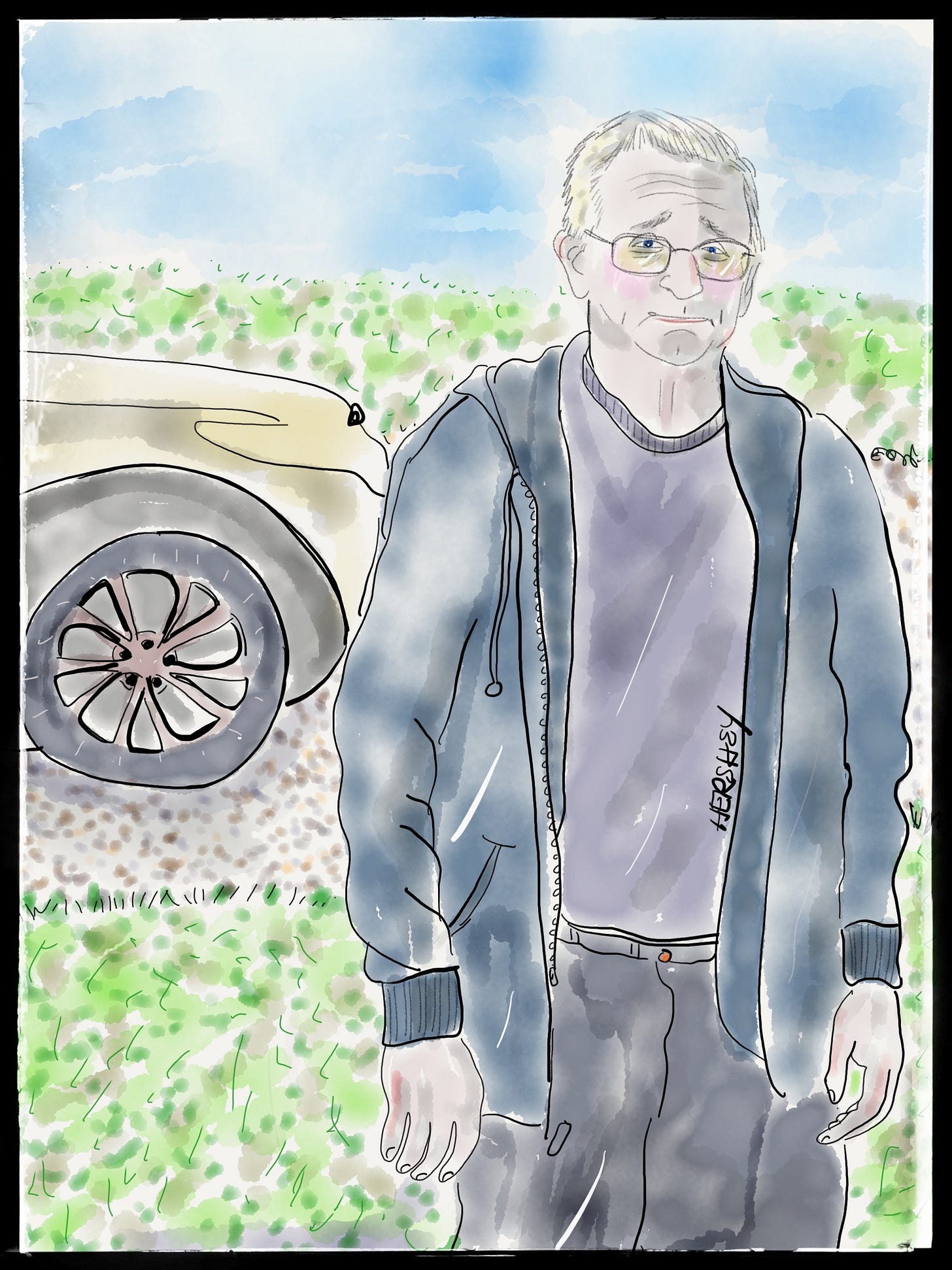

We ran into 86-year-old Dwayne walking his dog at Pipestem State Park in West Virginia. His younger wife was nearby, busy cleaning up the rentable bungalows at the state campground. Dwayne’s a retired coal worker who spent years running cars down in the mines. He told us he walked away from the mines early - not for leisure, but in the wake of a sudden, jarring silence after his brother-in-law was killed in a freak accident at the same mine. For Dwayne, the mountain had suddenly become a monument to loss. When the talk turned to bringing the mines back to life in West Virginia, Dwayne didn’t seem convinced. He was blunt about his doubts and, although he had voted for Trump, he had plenty of misgivings, giving a little shrug and tossing out, “We’ll have to see what happens,” in a tone that said he wasn’t holding his breath. We shared a moment of understanding. Getting older, it’s tough to just stay on the sidelines while the world changes around you.

Prologue

It’s been awhile. The trip we write about below took place in October of 2025. For that, we ask your forgiveness. But as you read this, you will understand why.

In early October, 2025, Jenny and I left the unrelenting hum of New York City for another bicycling adventure. We began driving south toward Blacksburg, Virginia, and as we approached the mountains we could feel the familiar shift: the way the ridges of the Appalachian Highlands have a way of making everything else feel small, the way the horizon softens into layers of blue and charcoal, and the way time seems to stretch out on the glorious New River as it winds north through so many valleys on its way to the Ohio River. It is a transition not just of geography, but of pace, as the jagged concrete canyons of Manhattan transform into the ancient, weathered peaks of the Blue Ridge, where the silence is heavy with the weight of history and an uncertain future.

We came for the rhythm of the pedals and the quiet of the mountain passes. Yet, as we left our car in Blacksburg and biked through Pearisburg and across the West Virginia line toward Princeton, we found ourselves pedaling straight into the heart of a different kind of landscape: one defined by tension brought on by the confluence of both a failing healthcare system, and a deteriorating lack of disaster preparation - both of which are gathering like a dark storm over the Appalachian Highlands.

Coal

In this region, the “fossil fuel economy” is the skeleton of the community. As coal production has declined - falling by more than 50% in West Virginia alone over the last two decades - the tax base that once supported schools and clinics has evaporated. For men like Dwayne, the “disinformation” campaigns about climate science aren’t just corporate PR; they are a desperate attempt to keep the lights on in a world that seems to be moving on without them. To make matters worse, the decline of coal has pit these communities directly against the hits coming at them through the “one big beautiful bill” (omnibus budget bill, or OBBBA), ironically passed on July 4 of this year.

After all, when a region’s primary wealth-generator (such as coal mining) disappears, leaving many so folks dependent on Medicaid, how will they satisfy new work requirements or afford the premium spikes of a federal budget bill that will soon require them to pay for something they cannot possibly afford? Fortunately, that won’t happen until 2027. Still, a lot of people in this area are very worried.

After reaching Princeton, WV, we biked up to Pipestem State Park, a place of immense beauty where the cliffs drop away into the Bluestone River Gorge and peaks to the west recede into infinity. Above: Jenny takes in the view to the east. Below: Although one cannot see the gorge from the Lookout Tower at Pipestem State Park, park, the views to the west are superlative.

Everywhere we looked as we bicycled out of Blacksburg toward Pearisburg and beyond, the land was gorgeous, made even more striking drenched in sunlight under deep blue skies. The local roads were almost empty, and the loudest sounds were roosters crowing or dogs barking, with only the occasional buzz of a chainsaw, the low hum of a tractor, or distant gunfire from hunters and shooting ranges. Every so often, we’d catch the smell of smoke from wood stoves and fireplaces. Most of the homes were small and often in need of repair, and most of the folks we passed seemed to be getting by on very little. The economy felt unmistakably hardscrabble.

Had we taken this trip several decades ago, the stretch between Princeton and Tazewell wouldn’t just have looked different; it would have felt like a different world. Back then, people called nearby Bluefield “Little New York” for its early skyline and the constant sense of motion in the streets, a reputation built during the coal boom years when the city was one of the first in the region to have a real downtown profile and busy nightlife. In the 1950s, about 21,500 people lived in Bluefield, West Virginia (currently there are 9,000) and the prosperity spilled over so strongly that Graham, Virginia - right next door, voted to rename itself Bluefield, Virginia, just to share the identity and the promise of that boom. For a time, the city boasted more cars per person than almost anywhere else in the country, which meant that “five o’clock traffic jams” were already part of daily life here long before most American cities knew what that felt like.

Just to the north, in McDowell County, WV, the numbers were even more staggering. In the 1950s, McDowell County was home to over 100,000 residents (currently about 16,800 people live there, and the trend is downward). It was the coal-producing king of the nation. Nearby Tazewell County, (our destination that day) in Virginia was a major player too, with a population and economy that stayed robust as long as the railroads were hauling out “black gold.” Back then, schools were the heartbeat of the community. In Bluefield, Bluefield State University (originally a historically Black institution) thrived as a residential campus. However, the school’s trajectory shifted toward a commuter model following a 1968 bombing and the era's intensifying racial tensions. Across Mercer and McDowell counties, there were dozens of local elementary and high schools in nearly every hollow, compared to today where West Virginia has seen over 70 public schools close since 2019.

Economically, it was a “feast or famine” life. When coal was up, the money was better than just about anything else a person could do without a college degree. In 2015, even as the industry was sliding, a miner could still make around $55,000 a year. But while the wages were high, the wealth didn’t really stick. The downtowns were full of businesses - opulent hotels like the 12-story West Virginian and bustling department stores - but much of that life started to drain away when Interstate 77 was built and the Mercer Mall opened in 1980, pulling commerce away from the old town centers. The most painful blow recently was when the Walmart in McDowell County shut its doors in 2016. It wasn’t just about losing 140 jobs; it was the loss of the only place many people could get fresh food without driving an hour over winding mountain roads.

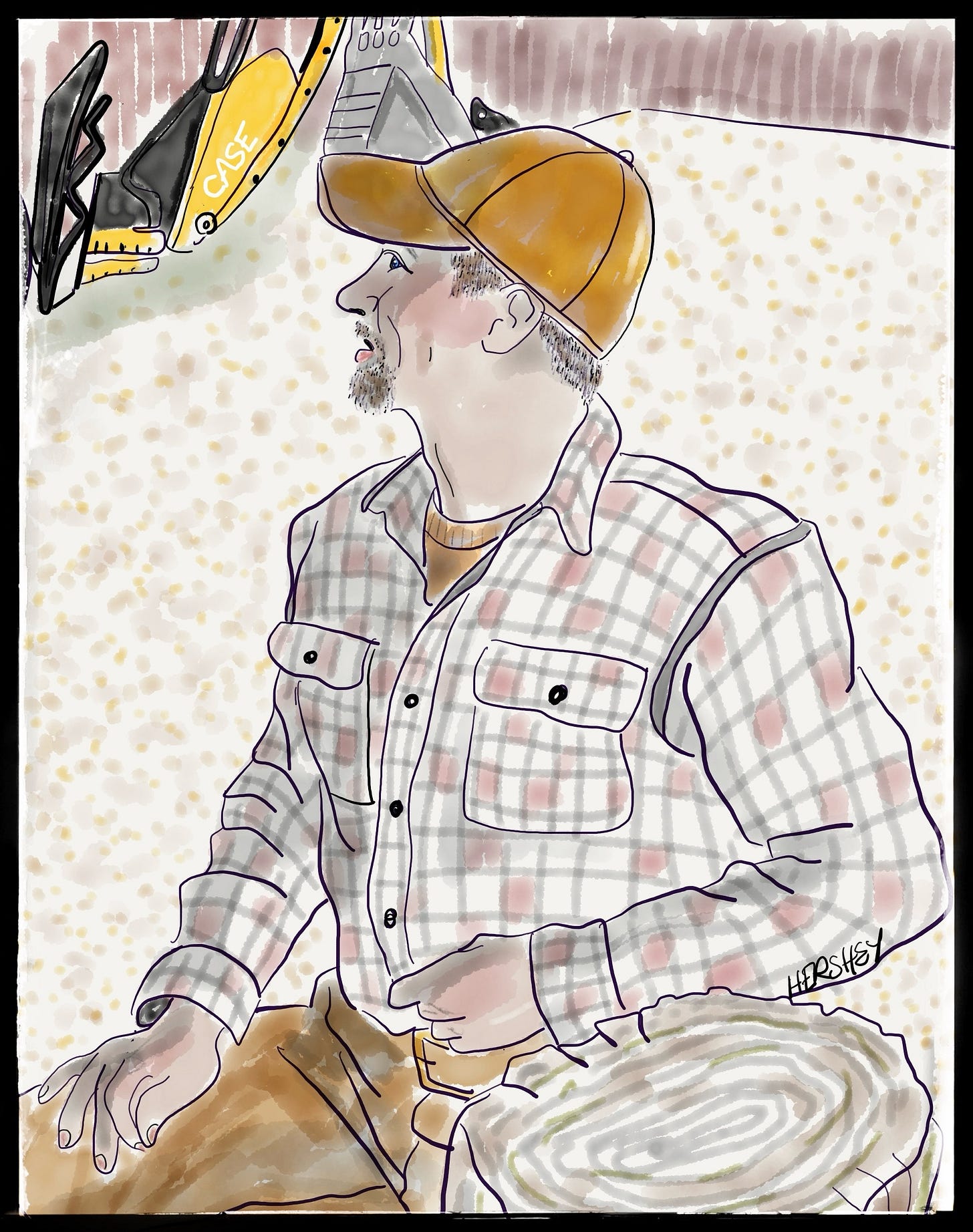

We met Robert out working in Pipestem State Park in West Virginia, where he was helping keep the trails in shape and welcoming for visitors. Robert comes from a long line of coal miners—a family tradition built on hard work and grit. But with the mines all closed down, folks around here don’t have as many options as they used to. Some, like Robert, find seasonal jobs maintaining the parks as West Virginia tries to grow its tourism business, even as the long-term future of these parks feels uncertain in a changing political landscape. West Virginia is especially exposed because about half its budget comes from federal dollars, which leaves park infrastructure and local jobs vulnerable as national support for environmental and disaster grants is pared back. Others around Pipestem head to the federal prisons for work, but in October of 2025 during the government shutdown, those jobs weren’t paying, hitting this area hard. Still, Robert loves working hard and takes pride in helping make West Virginia look its best for visitors, hoping the state’s natural beauty brings some new opportunities for everyone, even as he quietly wonders if he’s part of the last generation that will get to care for these woods.

Decline

People often ask why the coal industry didn’t see the writing on the wall or at least help the region come up with a “Plan B.” In reality, it was a mix of bad luck and some pretty cold corporate math. One of the biggest roadblocks was the fact that the people living there didn’t actually own the land they lived on. In McDowell County, just ten out-of-state landholders own over 60% of the private land. Since these companies only cared about what they could dig up, they weren’t exactly lining up to sell land to other industries—especially anyone who might compete for workers or push for higher taxes to fund better schools. Historically, coal companies were even accused of running “coal camp schools” that only taught the specific skills needed to pull coal. It worked for a while, but it left the workforce totally stuck once the mines started drying up.

The industry also ran into a “seismic shock” no one saw coming. Between 2011 and 2016, fracking took off, and suddenly cheap natural gas made coal look way too expensive overnight. Employment crashed by 50% in only five years. Because there had been so little investment in “human capital” - things like tech training or higher ed - there wasn’t much for people to fall back on. For generations, the mindset was that coal would always be there. By the time everyone realized it wouldn’t, the infrastructure was already falling apart. The young people with the most options had already packed up for the cities, leaving the region to figure out a comeback that still feels a long way off.

Mud Fork Road about 10 miles north of Bluefield, WV. just before the hill became steeper. The green ball-like shape on the road in the foreground is an American walnut. They are a definite biking hazard in the Autumn in the Appalachian Highlands. Often falling in batches, each one has a hard nut inside. Although we have no idea if Jenny hit one of these (we’d been dodging them for days), hitting a hard, round walnut with a bicycle tire, especially at the wrong angle, can cause the tire to shoot in an unexpected direction or the bike to slide out from under the rider, leading to a fall or accident. We had also biked alongside running deer that, on more then one occasion, had bolted across the road right in front of us. On rural roads in the Appalachians, plants, animals and large rocks are far greater hazards than cars or trucks. Yet, it’s worth noting that 96% of bicycling fatalities are caused by collisions with moving vehicles.

The beauty of the ride turned into a blur about ten miles northwest of Bluefield. I’d gotten a head start on Jenny during a long descent, coasting to the bottom and pulling over to wait. Jenny stops to chat with everyone - she has a gift for finding the story in a stranger, a trait that usually adds hours to our itinerary. When she didn’t appear after a few minutes, I simply assumed she had stopped to talk to a local about the wildflowers or the quality of the mountain air. I started pedaling back up the hill, fully expecting to find her laughing with a new friend.

But as I rounded the bend, I saw her in the distance. She was indeed standing next to her bike talking to a man I’d later know as Bob, who had rushed out after hearing her screams. As I got closer, the sunlight hit her face, and the air just left my lungs. Bob asked if I was Michael - Jenny had apparently been calling for me - and I managed to blurt out a “Yes!” just as I noticed the blood on Jenny’s face, tracing jagged lines down her cheek. Her glasses were sitting totally crooked, the left temple arm snapped clean off. The side mirror on her bike was smashed.

Bob helped me get her to the porch of his little cabin nearby. Once I got the bikes off the road, I sat Jenny down, my hands shaking as I tried to figure out how bad it was. She was a mess—cuts, deep bruises, road rash—but it was that vacant, flickering look in her eyes that really got to me. She was talking, but she was confused and couldn’t tell me what had happened. I learned later that was a classic sign of post-traumatic amnesia, a protective shutter the brain pulls down when the trauma of the moment exceeds its capacity to process it. To this day, the accident is a total blank for her.

Bob ended up being our lifeline. He is a bit of a hermit, but I was so panicked I didn’t even notice the effort it took for him to step up. He knew there was an urgent care at the Walmart in Bluefield, Virginia, about ten miles south. We stashed the bikes in his shed and he drove us toward town, calling his neighbors, Keith and Karen, to help us figure out how to get our gear back later. Interestingly enough, they were actually at the October No King’s Day protest, part of a crowd of about 200 people. Even in the middle of a crisis, those small-town connections were weaving themselves together.

Inside the Walmart, the quiet mountain air was replaced by the sterile hum of the clinic. We spent most of our time just filling out forms, but when the nurse finally saw us and Jenny explained she didn’t know how she fell, the nurse stopped her cold. “I can’t treat you,” she said. “You must have blacked out. You have to go to the ER five miles down the road.” I called Bob back, and luckily, he was still close by. He agreed to get us to the ER, but after that, he had to head home. We were on our own, hoping the Keith and Karen we had not yet met would help us track down our bikes and get to a motel for the night.

Dr. Duff is a retired Air Force officer who runs a seriously tight ship at the Bluefield, Virginia ER. The facility is small and sits attached to an old, shuttered hospital that’s been turned into a dorm for Bluefield State—it was literally Jenny’s only option within about an hour. Now, Jenny is a self-admitted control freak, and being in a situation she couldn’t control didn’t sit well with her. She sized him up immediately and tried to push back when he insisted on checking if a stroke or heart attack had caused the crash. Dr. Duff didn’t blink; he made it crystal clear who was in charge, and it definitely wasn’t Jenny. Looking back, we’re both so grateful to him. Even in the middle of treating her, he had to jump out to intubate a very sick patient who’d just come in by ambulance before he could finish stitching up a deep gash on Jenny’s elbow. The whole ordeal really put the rural healthcare crisis in perspective for us. It shined a light on the quiet heroism of people working brutal hours in tiny, understaffed clinics that too many politicians seem perfectly fine forgetting about.

OBBBA

As we rushed toward Bluefield, the rural healthcare crisis stopped being a statistic and became our reality. Back in 2020, the Bluefield Regional Medical Center basically died. It used to be a full-service hospital, but now it’s been scaled back to just a standalone emergency room. It’s a ghost of its former self - a “feeder” facility designed to stabilize you just long enough to ship you an hour away to a bigger center in Princeton.

Inside, after a long period of filling out forms, we finally met our doctor. Dr. Duff had the steady hands of someone who’d seen combat, but you could still see the strain in his eyes. He’s stuck in a system where Americans pay the highest prices in the world for care - not because we’re getting more for our money, but because of administrative bloat and monopoly pricing. In a place like Bluefield, the “market” simply decided that a full hospital wasn’t profitable enough to keep around. But Bluefield is just one piece of a much larger puzzle. In the counties surrounding Tazewell, the healthcare map is effectively bleeding.

In McDowell County, nearly half of the 16,000+ residents rely on Medicaid. Welch Community Hospital is the only line of defense for a population that literally gave their lungs to the coal mines. Back in Tazewell County, places like Clinch Valley Medical Center are trying to serve an aging population that’s becoming more isolated by the day. And while Mercer County still has the Princeton Community Hospital, it’s being crushed under the weight of all the smaller clinics that have closed nearby.

The “One Big Beautiful Bill” targets these exact people. Even though the Medicaid cuts and those new co-pay charges won’t officially kick in until 2027, anxiety is already thick in the air. For a family in McDowell or Mercer, a new monthly co-pay isn’t just a small fee; it’s a wall. When people can’t swing that cost, they stop seeing the doctor altogether. They wait and wait, until “the silence” turns into a full-blown emergency.

While Jenny was getting patched up, I managed to connect with Keith. Together, we worked out a plan to get our bikes over to the local Quality Inn where I’d booked us a room. Over the next few days, I got to know him a bit better. Keith’s a retired coal engineer and project manager. He’s also a long-time Democrat who traded in his desk chair for a quieter life raising cattle and farming bees. He’s a Virginia Tech guy through and through, and he spent the bulk of his career at Pocahontas Mine No. 3, right on the border near Bluefield. The mine is a total legend in these parts. Opened back in 1882, it was the crown jewel of the Pocahontas Coalfield. They pulled out a specific kind of high-quality, “smokeless” coal that was a massive deal for steelmaking and even fueled the U.S. Navy during the steamship era. At its peak, the place was a huge economic engine; back in the 1920s, about one in five West Virginia miners were working in the Pocahontas region. It’s basically the reason towns like Bluefield exist in the first place. Because the demand for labor was so high, it drew in a really diverse mix of people from all over, which shaped the local culture for decades. Today, the mine is a National Historic Landmark, but sitting there talking to Keith made all that history feel a lot more personal than any plaque ever could.

That morning, Keith and Karen hadn’t been tending bees. They had been in Bluefield protesting the overwhelming power and abject cruelty of the current administration. People had gathered to protest - among many other things - the top-down mandates of the “One Big Beautiful Bill”, which they see as a royal decree from a distant capital that doesn’t understand the topography of their lives.

There is a deep irony here. The marchers were protesting “government overreach,” yet they are the ones who will be most devastated when the federal government retreats. The OBBBA takes aim at Medicaid and Medicare with surgical precision, adding work requirements and means-testing that assume a level of economic flexibility that just hasn’t existed in these mountains for decades. Across all of West Virginia, about one in three people rely on Medicaid for their basic health. While those cuts and new co-pay charges don’t officially kick in until 2027, you can already feel the anxiety on the ground. For a family out here, a new $20 or $40 monthly co-pay isn’t just a minor tweak to the budget - it’s a wall. When people can’t swing that cost, they put off going to the doctor until a small problem turns into a total catastrophe. That just puts more weight on those standalone ERs, like the one in Bluefield, which are already stretched to their absolute limit.

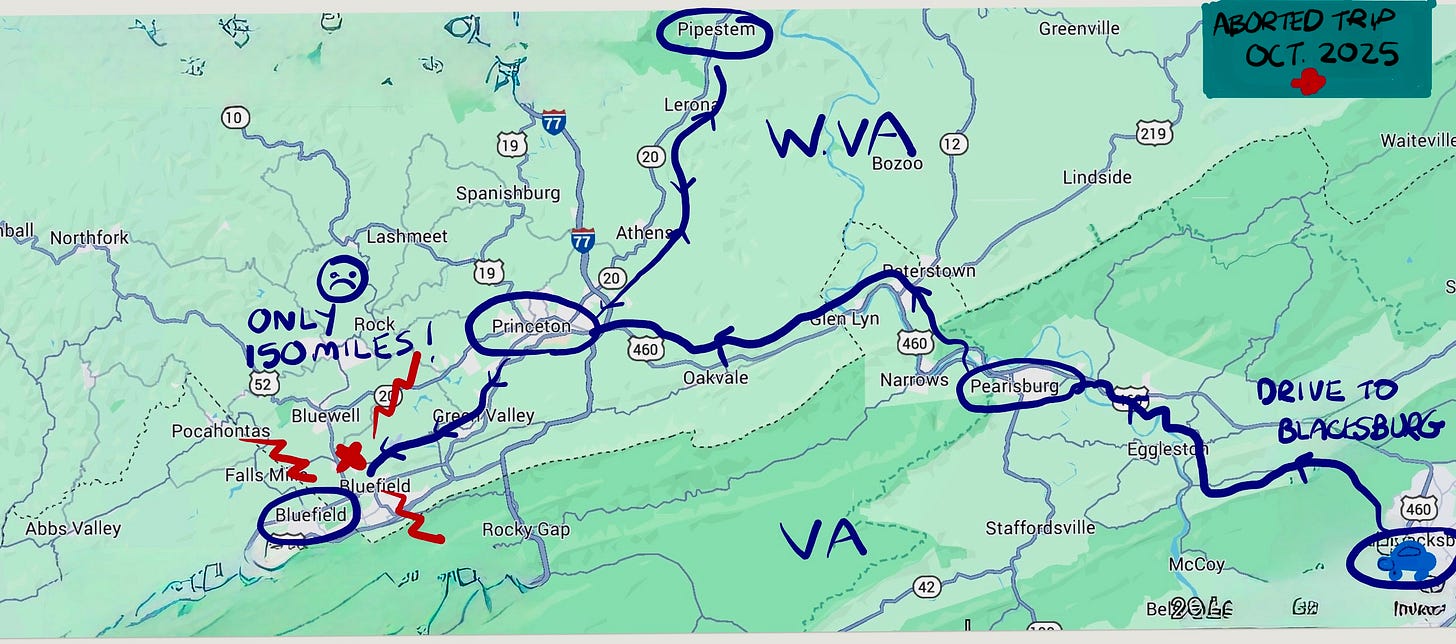

A photo of Jenny convalescing in our motel room the day after her accident. Concussions are no fun at all. Although her CT scan was clear and other tests showed no evidence of a heart issue or stroke, she wasn’t able to travel for several days. In the interim, Karen drove me over to the local Walmart to shop, and a few days later Keith and Karen drove me to Blacksburg—about 70 miles by freeway, or roughly 150 miles by back roads—to get our car. Once home, Jenny got an MRI (also clear) and saw a neurologist, who said there were no problems with her memory or intellectual capacity. She has had some issues with vestibular dizziness and has had Epley maneuvers to address that. She’s also had superficial nerve pain and a slowly resolving subdural hematoma. But I’m pleased to write that she is almost back to normal and certainly not limited in any way. She’s already talking about the next trip, so stay tuned to carbonstories.substack.com. The next post will most likely be about biking the Delta to explore the environmental downsides of data centers in Mississippi, especially the copious amount of water each one requires for cooling.

FEMA

Yet, we are facing something even more threatening: the collision of failing hospitals and a collapsing disaster response system. This is especially true in the Appalachian highlands, a region that has become ground zero for extreme rain. The ancient, narrow hollows act like natural funnels, turning a heavy summer downpour into a vertical wall of water in minutes. Recent studies show these high-intensity storms are becoming the new normal, driving flash floods and landslides across the southern and central Appalachians.

The United States once had the gold standard for climate and weather research in agencies like NASA and NOAA. Their observational records clearly link a warming world to more extreme rainfall, yet their findings are increasingly treated like just another partisan opinion on Capitol Hill. It is a culture war that ignores physical reality even as the impacts pile up. Unfortunately for us all, the OBBBA leans into this skepticism by gutting FEMA’s reach, using budget cuts to shift more disaster costs back onto states and localities. One key move is to raise the “per capita” damage threshold - the mathematical bar a state must clear before the feds step in with Public Assistance. Currently, that statewide indicator is set at about $1.89 per person, which means West Virginia needs to show roughly $3.4 million in public damage before FEMA aid even becomes an option. Under the new proposals, that threshold could spike by as much as 400 percent, pushing the bar far beyond what many rural communities can reasonably clear after a localized disaster.

This creates a mathematical trap for places like Tazewell and Mercer counties. If a flood wipes out fifty homes and a few critical bridges, the total bill might not hit that new, inflated federal threshold. West Virginia, already strapped for cash from lost coal revenue and the costs of an aging population, would be expected to handle the recovery alone. But the state just isn’t ready for that kind of burden. When the next big flood hits, the community will find itself caught in a three-fold crisis where the infrastructure will fail, the healthcare system will fail, and the financials will fail. Roads will wash out and stay broken for years because the feds deem the disaster “too small” to help. Standalone ERs will get cut off by mudslides, leaving no place for trauma cases. Meanwhile, families already squeezed by new Medicaid co-pays will have no personal savings and no federal grants to rebuild their lives.

It makes you wonder how many more people we will lose in the next emergency because the “Golden Hour” of medical care is blocked by a mudslide on a road the government deemed too small to fix. The result will be a slow, silent emptying out of the region - a permanent silence where the land remains beautiful but living on it becomes untenable.

Keith and Karen’s bee farm on Mud Fork Road. It’s a beautiful place, and the honey is still sweet.

Epilogue

Jenny is healing, and I am so deeply proud of her extraordinary spirit. With the exception of the details of an accident she will probably never remember, her memory is as strong as ever. She is walking five to ten miles a day now, something she never would have done before this adventure. She’s going to be just fine.

But while Jenny heals, that “Silence Before” still hangs over the mountains. We love this land—the way the fog sits heavy in the hollows at dawn and the way the people here offer a hand before they even ask your name. We love the spirit of independence that drives a man like Keith to farm bees after a life in the coal industry. But we are terrified for them as we watch a disaster being built by hand, policy by policy. We are seeing a healthcare desert and climate vulnerability wrapped in a bill that calls itself “beautiful” while it strips away the very floor people stand on. These aren’t just budget shifts; they are a retreat from the American promise that we protect our neighbors in a crisis.

As we drove back toward New York, leaving the blue ridges behind in the rearview mirror, we realized that while Jenny’s concussion was temporary, the amnesia of our policymakers is much more dangerous. They have forgotten that in the mountains, when the water rises and the doctor is gone, a neighbor like Bob is the only thing left between life and death. But even the best neighbor cannot stop a flood or cure a concussion without the tools they’ve been promised. We have to wake up and see the warning signs. In these hollows, if we don’t fix the floor on which we all stand, the silence won’t stay peaceful - it will be followed by an apocalypse.

Stay vigilant! Thanks for reading. If you haven’t done so, please subscribe to this blog to follow our next biking trip.

This newsletter was written by Michael Chase, and illustrated by Jenny Hershey. Unless otherwise noted, all material is the copyrighted property of the authors, including all photographs and drawings.

Jennifer Hershey’s drawings can be enjoyed on Instagram.

Sources

Coal:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bluefield,_Virginia https://law.lis.virginia.gov/charters/bluefield/ https://coalheritage.org/page.aspx?id=108 https://drbrop.wordpress.com/2014/07/11/bluefield-a-wedding-of-two-communities/ https://visitmercercounty.com/blog/bluefield-natures-air-conditioned-city/ https://kids.kiddle.co/Bluefield,_West_Virginia https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/McDowell_County,_West_Virginia_Genealogy https://mcdowellcountycommission.com/history/ http://s1030794421.onlinehome.us/vacount/tazewellco.html https://www.kpbs.org/news/2013/10/17/the-whitest-historically-black-college-in-america https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/entries/536 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mercer_Mall https://wvpolicy.org/the-decline-of-mcdowell-county-and-the-future-of-coal/ https://wvmetronews.com/2016/01/28/walmart-closes-its-doors-in-kimball/ https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/jul/09/what-happened-when-walmart-left https://wvpolicy.org/tracking-public-school-closures-in-west-virginia/

Decline

https://wvpolicy.org/the-decline-of-mcdowell-county-and-the-future-of-coal/ https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/jul/09/what-happened-when-walmart-left https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/entries/1271 https://wvstatehousing.com/mcdowell-county-housing-needs-assessment/ https://minesafety.wv.gov/historical-statistical-data/mining-in-west-virginia-a-capsule-history/ https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=31392 https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-coal-paradox-why-the-industry-fell-and-how-the-region-can-rise/ https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2016/04/f30/wv_energy_profile.pdf

OBBA and FEMA

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/One_Big_Beautiful_Bill_Act https://www.astho.org/advocacy/federal-government-affairs/leg-alerts/2025/one-big-beautiful-bill-law-summary/ https://www.feldesman.com/the-one-big-beautiful-bill-act-is-approved-by-the-senate-devastating-impacts-for-health-coverage-overall-some-silver-linings-for-fqhcs/ https://usafacts.org/articles/how-will-the-obbb-impact-medicaid/ https://www.congress.gov/crs_external_products/IN/PDF/IN12574/IN12574.1.pdf

Thank you, Michael & Jenny for these stories…the journeys are remarkable, as is Jenny ‘s story of recovery. As in prior writings, your stories are thoughtful & thought-provoking…thank you! Be well & enjoy what’s”next” for you two! Best wishes for safe travels! 💕Frani & John